Struggling With Sleep? Here Are My Top Five Tips for Better Rest

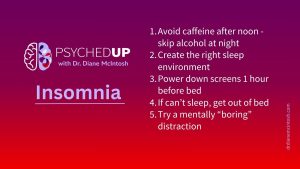

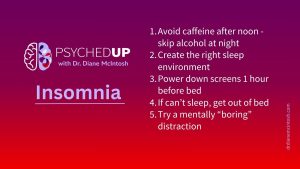

I want to share my top five “sleep hygiene” habits that can support healthier sleep. They won’t solve chronic insomnia on their own, but they are essential ingredients for better rest.

The majority of mental healthcare services in Canada (and the US) are provided by non-psychiatrists, usually primary care practitioners (PCPs). When we look around the world, roughly a third of visits to a PCP are by individuals with a diagnosable mental illness, representing one of the most important groups to seek medical advice.,

Yet one-half of Canadians either can’t find a PCP or are unable to get a timely appointment. And all types of healthcare practitioners are experiencing high levels of burnout – with levels amongst physicians nearly doubling during the pandemic.

For patients who would benefit from a specialist psychiatric consult, the delays are daunting. Family doctors describe psychiatrists as the most difficult specialists to access. In a phone survey performed in Vancouver several years ago, researchers tried to book a real patient for a psychiatrist consultation from a PCP’s office. Out of 230 psychiatrists in private practice, only six would see the patient on short notice (within 2-3 months), illustrating the significant access challenge. This poor access has only worsened with time.

It’s not surprising that many turn to the emergency room (ER) to rapidly access psychiatric care. But when someone experiencing acute psychiatric symptoms goes to an ER, these visits are often experienced as unpleasant and unhelpful.

ERs may provide entry into the system for people in crisis, but cannot be relied upon as a primary solution to diagnose or treat a mental illness, even if it is severe. One study found that, of patients who presented at the ER following a suicide attempt, only 40% were able to see a psychiatrist within six months of their visit. [1]

So what are we to make of this? The majority of Canadians struggling with a mental illness, regardless of the severity, don’t have timely access to a general practitioner to treat them. Even those with the most severe symptoms and functional impairment can’t get the specialized help they need. In many places, the only way to access to a provincially-funded psychiatrist working outside a hospital is through a referral from a family doctor, yet the number of community-based psychiatrists are dwindling and they often have years-long waitlists, or no longer offer an option to wait, as they’re nearing retirement.

The lack of access to a PCP or a psychiatrist is only one of the many barriers that obstruct the provision of high-quality mental healthcare. Inadequate compensation for community-based practitioners, lack of collaboration between practitioners and between healthcare systems (e.g. lack of continuity of care between community-based clinicians and those in hospitals), inadequate continuing medical education/ habit-based prescribing and inadequate access to specialist guidance are also critical barriers.

Importantly, but not often acknowledged, is the presence of stigma amongst healthcare professionals, including within psychiatry (see my post about stigma for more on this topic). Practitioner stigma regarding mental illness has a powerful impact on patients and their families and can include negative attitudes and behaviours, lack of knowledge, skills and awareness, and therapeutic pessimism.

Without strong medical leadership and ongoing high-quality medical education, such stigma too often pervades the culture of healthcare settings, including hospital emergency and psychiatric units. Clinician burnout is associated with heightened cynicism and a loss of compassion, so the pandemic’s toll on practitioner’s mental health has undoubtedly worsened the burden of stigma for patients.

Unlike most areas of medicine, psychiatry lacks biological markers (laboratory and imaging tests) that reliably support a diagnosis and help determine the best treatment approach. Without objective biological tests, making an accurate diagnosis and finding an effective, tolerable treatment is inexact and more complex and time-consuming.

There is a care gap between the clinical goals outlined in evidence-based guidelines for the management and treatment of mental illness and actual clinical practice. Robust clinical decision support systems would provide healthcare practitioners with best-practice information at the point of care (when they’re seeing their patient), but these tools are profoundly lacking. This is where we have the greatest opportunity to support PCPs, which in turn will help improve the health, functioning and quality of life of patients living with a mental illness.

All areas of medicine, including psychiatry, have demonstrated the value of algorithm-based care, which is more accurately defined as evidence-based guidance for clinical decision making. Findings from the German Algorithm Project (GAP) demonstrated that employing a highly structured decision-support program for the treatment of depression was associated with the need for fewer medications and a shorter time to symptom remission, compared with treatment-as-usual. Such approaches have been shown to improve patient’s overall well-being (symptoms and functioning) and have demonstrated cost-effectiveness.

Clinical decision-support programs must be expert-validated, easy to use, educational, provide options to clinicians and their patients and fit into a clinician’s workflow. Additionally, the guidance must be personalized for each patient, because every brain has unique needs. By employing the latest scientific research and expert guidelines and delivering this information to a busy clinician, immediately and seamlessly, using innovative, secure technology, everyone wins.

Clinical decision support programs do not replace a healthcare professional – they marry the art and science of medicine, by offering expert guidance that helps a PCP to rapidly provide better, more personalized care. Getting the diagnosis right and providing the most effective treatment to each patient should also help clinicians to have more time, energy, confidence and hope. These attributes support compassionate care, which should be at the heart of every interaction we have with our patients.

This blog post is part of a series looking at the state of our mental healthcare system and ways we can create sustainable change to improve quality and outcomes for anyone impacted by mental illness.

I want to share my top five “sleep hygiene” habits that can support healthier sleep. They won’t solve chronic insomnia on their own, but they are essential ingredients for better rest.

There’s something about flipping the page on the calendar from December to January. For many of us, the beginning of a new year represents a clean slate. So, if you find yourself in the mood to take that time to pause and reflect after the holidays, here are a few tips on making smart New Year’s resolutions.

The holidays can be stressful. Here are a few thoughts on how to make the most of what can be a most wonderful time of the year.

Please provide your contact information in the form below. It helps if you provide enough detail in your message so we can help. We look forward to hearing from you!

Thank you for your message. We will respond to your email promptly.