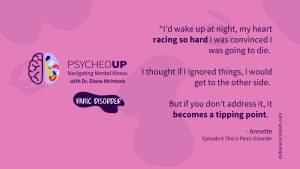

Understanding Panic Disorder: Symptoms, Treatment, Bravery in Asking for Help

Panic disorder, which affects 3.7% Canadians, is “fear gone wrong.” With appropriate therapy and medication, people with panic disorder can keep symptoms in check. Summary of “This is Panic Disorder”, Episode 6 of PSYCHEDUP Podcast.