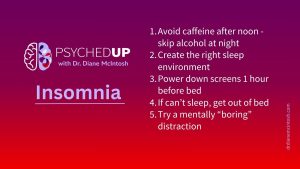

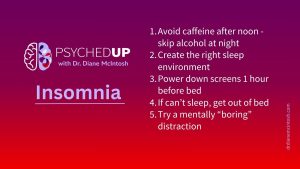

Struggling With Sleep? Here Are My Top Five Tips for Better Rest

I want to share my top five “sleep hygiene” habits that can support healthier sleep. They won’t solve chronic insomnia on their own, but they are essential ingredients for better rest.

Silken Laumann exudes confidence. A champion rower who’s won three Olympic medals for Canada, she’s known for her tenacity and courage. Just a few months before the 1992 Olympics, a German team sliced into Laumann’s shell during training, causing a leg injury that was so devastating, it looked like her career might be over. Remarkably, after enduring multiple surgeries and requiring a cane to maneuver on land, she went on to win the bronze medal for Canada.

Despite her incredible achievements on the water, Laumann waged a private battle with depression, a condition she initially didn’t recognize.

“I really didn’t understand that what I was experiencing was mental illness,” said Laumann. “My first clue was rage,” adding she often found anger welling up while parenting her two children. “I would feel so much rage in moments with my kids, with my little, beautiful children who weren’t doing anything wrong, but it would just come up so fast, and then I would feel ashamed,” she recalls.

Laumann reflects on her difficult childhood, one she had never acknowledged. She never considered confronting what she now understands was childhood trauma. Instead, she channeled her anger into achievement—and was wildly successful. But below the surface, trouble was brewing.

The onset of depression, which affects about 15% of adult Canadians, is often insidious, says Dr. Diane McIntosh, psychiatrist and founder and CEO of RAPIDS Health. The symptoms—low mood, loss of interest or pleasure, appetite and sleep pattern changes, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt and difficulty concentrating—can creep up slowly, until they interfere with daily activities.

Worse, there are no objective tests – no brain scans, no blood tests – that can help to diagnose it, says Dr. McIntosh. Instead, clinicians rely on specific questionnaires to assess the presence, severity and impact of depression symptoms. “These specially-designed questionnaires can also help me to determine how much the symptoms are impacting my patient’s ability to work, participate in family activities, or to remain socially active. And, they can cast light on how depression is impacting their quality of life,” she says.

Once a diagnosis of depression is made, there are many treatment options that have the potential to give patients back their lives, says McIntosh. “The thing about depression is that it makes your brain believe that everything is hopeless, that you’re worthless, that there’s no path to peace,” she says. “But as a psychiatrist for 25 years, I can tell you unequivocally – that is a lie.”

“When it comes to depression, there is always a path ahead,” says Dr. McIntosh.

Laumann: “I think my mental health is excellent, and I say that cautiously, because I know that it can change really quickly. I think I’ve learned so much from my own personal journey, but also from listening to other people, and that knowledge has been accumulating. I’m feeling good, even though life is a bit chaotic right now.”

Laumann is a big believer in the power of storytelling. An author and speaker, she credits a big part of her recovery to understanding her own story and sharing her journey with others. “I have experienced firsthand that understanding your own story is actually kind of a way of taking your power back,” she says. She believes that by sharing her struggles, she can break through the stigma that surrounds depression and prevents many individuals from talking about it. “It’s not about navel-gazing or blame, it’s about understanding where you are now,” she explains. “As you understand it, it starts to make sense in your mind.”

There is no simple answer to what causes depression; the causes are not fully known or understood. All mental illnesses have biological, psychological, and social risk factors. Depression is no different. How we’re parented, our coping skills – or lack of coping skills – the education we receive and other life experiences are part of a psychological risk profile. There are biological risk factors: things like genetics, hormones and other brain chemicals. Social risks include day-to-day issues like financial security, safety, and the level of support we have from friends, family, coworkers. Of course, these risk factors overlap and influence each other.

Where does someone start the journey for help? Dr. Randy Mackoff, a Vancouver-based clinical psychologist, says he begins by sending patients back to their family doctor to ensure they rule out any underlying conditions that could be causing the depressive symptoms, such as an underactive thyroid or a vitamin deficiency.

Then he determines the severity of the symptoms. “One of the things I have found is that when people are experiencing a more severe depression, they can come to a psychologist frequently and they’re going to be frustrated, because they’re unable to make the changes that they really want to make,” he says. In these situations, he says, it’s really important that they see their family doctor to discuss medication.

Dr. McIntosh emphasizes that patients should persist in seeking help if they feel their symptoms are impacting their life, even if they face challenges when requesting treatment.

And, she warns, if an antidepressant is warranted, finding the right one for you can take time. “We have more than 20 antidepressants on the Canadian market, approved by Health Canada – they all work and they’re all safe,” she says. “But that doesn’t mean that they work for every person.” Plus, some have unpleasant side effects, from weight gain to sexual dysfunction.

She says that her job is to find the right treatment for each individual’s unique needs. Dr. McIntosh also tells patients that they should stay on an antidepressant for a year from the time symptoms resolve. “If you stop before that, you are much more likely to have a relapse. And after you’ve had two depressive episodes, you should stay on your treatment for at least two years,” she says, “because you’ve got about a 75 per cent chance that you’re going to have another depression.”

Participating in talk therapy, also called psychotherapy, can be invaluable, but it’s important that there’s a strong rapport with the therapist. Talk therapy can be more effective in tandem with medications in more serious depressions, says Dr. Mackoff. “That makes for a really good combination,” he says.

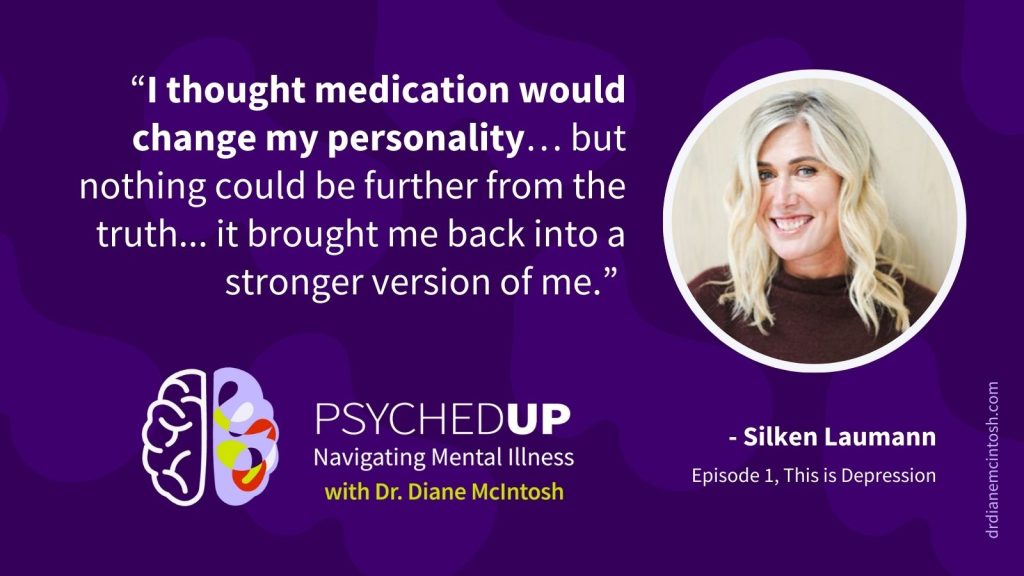

Ultimately, Laumann took advantage of both talk therapy and medication, but getting there wasn’t easy.

“I didn’t want to go on medication. Like a lot of people, I thought medication would change my personality… would change the essence of who I was as a person. But nothing could be further from the truth in my experience. It brought me back into a stronger version of me. I remember thinking, this is what it feels like not to feel sad. This is awesome.”

In Laumann’s case, she tried several antidepressants before she found the right one for her. She also began to make lifestyle changes, such as taking personal time if she needed it, exercising more, and not drinking coffee, which for her seemed to have a destabilizing effect.

Like many people, Laumann tried to stop her antidepressants many times over the years, but every time she felt the devastating impact. With support, Laumann was able to get the help she needed to recover from depression.

And she wrote a book. “I was terrified of publishing the story, putting it out there, changing the perception of who I was, because people saw me as this four-time Olympian, world champion, and I was showing where I was weak,” she says.

But a surprising thing happened on Laumann’s book tour. “People would share their experiences with me.” And she realized that sharing her story made people feel less alone in their diagnosis.

Her depression now under control, Laumann is looking forward to her future. “Whatever comes in my life, I feel capable of working my way through it,” she says.

Listen to the depression episode of the PSYCHEDUP podcast.

This blog post is part of a series looking at the state of our mental healthcare system and ways we can create sustainable change to improve quality and outcomes for anyone impacted by mental illness.

I want to share my top five “sleep hygiene” habits that can support healthier sleep. They won’t solve chronic insomnia on their own, but they are essential ingredients for better rest.

There’s something about flipping the page on the calendar from December to January. For many of us, the beginning of a new year represents a clean slate. So, if you find yourself in the mood to take that time to pause and reflect after the holidays, here are a few tips on making smart New Year’s resolutions.

The holidays can be stressful. Here are a few thoughts on how to make the most of what can be a most wonderful time of the year.

Please provide your contact information in the form below. It helps if you provide enough detail in your message so we can help. We look forward to hearing from you!

Thank you for your message. We will respond to your email promptly.