Struggling With Sleep? Here Are My Top Five Tips for Better Rest

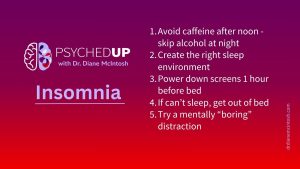

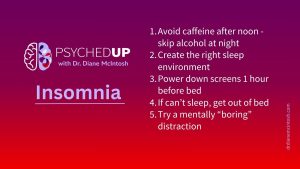

I want to share my top five “sleep hygiene” habits that can support healthier sleep. They won’t solve chronic insomnia on their own, but they are essential ingredients for better rest.

Several years ago, I slowly came to the realization that I was burned out. While this was no surprise to anyone who loved me, it came as a complete shock to me. I didn’t know much about burnout, so it wasn’t something I’d even considered, although I knew something was wrong. I was easily frustrated, I didn’t have the patience I once had and caring for my patients, which I had always felt was a calling and my passion, was increasingly difficult. By difficult, I mean tiring, draining. I faced my work days with dread. The weekend was never long enough. I wasn’t my usual enthusiastic, effervescent self.

Burnout is not a mental illness, but instead it’s a syndrome related to work or occupations where others’ needs come first, and where there are high demands, few resources and a disconnect between a worker’s expectations and their experiences. While it’s usually blamed on the sufferer, it’s the system or workplace that’s just as responsible, if not more so, for provoking burnout. The signs of burnout include feeling emotionally exhausted, a declining sense of accomplishment and growing cynicism towards the system you’re working within. If nothing changes, these issues usually worsen over time.

My burnout was in part due to working in a medical system where I learned, through bitter, painful experience, that a patient’s needs weren’t always the priority.

Sometimes, when a patient experienced a serious exacerbation of their mental illness, I would reluctantly recommend they consider hospitalization.

Other times, I couldn’t offer them the choice, because they were so ill I was concerned they posed an imminent risk to themselves or someone else. In that case, unless they agreed to be admitted voluntarily, I’d have to certify them, which requires them to be seen at the closest emergency room (ER) and admitted. Whenever that happened, I’d call the ER to let them know I was certifying my patient, fax over the form and a clinical note, and send them with their loved one, one of my team members, or a close friend, who could act as a support and a source of collateral information.

From countless interactions with hospital ERs over nearly twenty-five years, with rare exceptions, I learned that whether my patient felt heard, understood, safe or cared for didn’t seem to matter at all. That shouldn’t have come as a surprise, as I was treated in a similar manner by my colleagues. My notes were usually ignored. Colleagues rarely, if ever, returned calls.

Patients I’d known for years, who I’d reluctantly certified, based on my experience with them and collateral from their loved ones, were often decertified and discharged. I was never informed. Often, a distraught family member contacted me to tell me my patient was sent home. They would share, with bewildered frustration, that no one wanted to hear their concerns. They felt ignored, indignant and terrified for their loved-one’s safety.

My burnout came from a pile-on effect of years of frustration interacting with a broken system.

My belief in fairness and justice – not just conceptually but practically – was incompatible with my experience. Knowing that sending my most ill, vulnerable patients to the hospital wouldn’t make them safer, no matter how hard I tried to protect them, provoked a moral injury. Fighting a lonely battle to get my patients the safest, most tolerable treatments, to hold decision makers accountable, and to insist on following science, added fuel that intensified my burnout.

I felt responsible for my patients, and, perhaps naively, I also felt responsible for my profession and the behavior of my colleagues. I wrote op-eds. I stood up for my patients, arguing with Pharmacare and insurance companies. I mostly felt appreciated by my patients and their families- we were on the journey together. But on the rare occasion when I was criticized by a patient or a family member, despite doing everything possible to help, their angry words started to stick to me and I knew I‘d had enough. I understood they were frustrated with the diagnosis, the treatment or the system- so was I. But I wasn’t prepared to play offense and defense. I had to stop.

Regardless of the cause, to make my way through burnout I had to accept responsibility for my role in its development and change my approach to work. I did this by identifying patterns of behavior that were clearly making me vulnerable. I took my responsibilities seriously and I never wanted to disappoint anyone, including my patients, colleagues, and anyone I collaborated with. But I always took on too much, even when I was already overloaded, and I had serious FOMO – new opportunities to learn, share and grow have always felt impossible to decline. Critically, I was prioritizing everyone except those who meant the most to me- my family.

I know I’m not alone. Perhaps some of the clinicians who behaved so poorly were also dealing with burnout. A 2017 Canadian Medical Association survey found that 30% of physicians reported a high degree of burnout. By November, 2021, that number had risen to 53%. That number is frightening, because of its implications for the healthcare system. The fact that more than half of my colleagues are struggling with emotional exhaustion and hopelessness, and losing their compassion, is a disastrous harbinger of what is to come- more medical errors, greater harm to patients, less satisfaction with the care experience, and even greater barriers to access care, as doctors, nurses, pharmacists and other healthcare professionals simply walk away from their profession. Despite the changes I’ve made in my professional life, I haven’t fully recovered from burnout.

Breaking out of a burnout cycle is difficult. First, I had to recognize I was burned out. Then, I had to make a plan to change. Finding that path can take time, because changing how you think, feel and behave takes a great deal of time and effort. If I didn’t change that, I was bound to be burned out again. Third, addressing burnout requires system change, as it’s a workplace challenge, not just a problem for a worker to solve. That aspect of recovery was beyond my control, so I had to change the work I do.

Since I withdrew from my clinical practice, I’ve had to say no to countless people who desperately needed my help, which is incredibly difficult to do. I have no place to send these people, and access to high-quality mental healthcare is worsening by the day.

I’ve shifted my professional focus to supporting my colleagues who bear the greatest weight of mental healthcare delivery, family doctors, and increasingly, nurse practitioners. I’m working to provide them with tools that will support the quality of their psychiatric care.

By building their confidence and lightening their load, I hope to reduce their risk of burnout and help maintain or restore their compassion. Access to an informed, caring primary care provider is the foundation of our healthcare system. Without them, countless Canadians will continue to needlessly suffer and die from treatable mental illnesses.

2025 Update: You can learn more about my work with RAPIDS Health on the RAPIDS website. RAPIDS is a Decision Support System that provides guidance pertaining to the importance of an accurate diagnosis and appropriate, personalized treatment for mental illnesses. By supporting diagnostic rigor and providing personalized treatment guidance, RAPIDS can reduce symptom severity and illness duration and contribute to a patient’s return to full function, more quickly than treatment-as-usual. Currently, RAPIDS reviews an individual’s diagnosis, and, if it is not supported by validated clinical scales, suggests the clinician consider an alternative diagnosis. RAPIDS provides treatment guidance, for the clinician to consider with their patient, for generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, insomnia and ADHD. RAPIDS also reviews current medication information – including recommendations for initiating, optimizing, augmenting, and switching treatments. Learn more>>

This blog post is part of a series looking at the state of our mental healthcare system and ways we can create sustainable change to improve quality and outcomes for anyone impacted by mental illness. I also do a podcast covering conversations with Canadian leaders on possible ways forward in mental healthcare transformation.

I want to share my top five “sleep hygiene” habits that can support healthier sleep. They won’t solve chronic insomnia on their own, but they are essential ingredients for better rest.

There’s something about flipping the page on the calendar from December to January. For many of us, the beginning of a new year represents a clean slate. So, if you find yourself in the mood to take that time to pause and reflect after the holidays, here are a few tips on making smart New Year’s resolutions.

The holidays can be stressful. Here are a few thoughts on how to make the most of what can be a most wonderful time of the year.

Please provide your contact information in the form below. It helps if you provide enough detail in your message so we can help. We look forward to hearing from you!

Thank you for your message. We will respond to your email promptly.