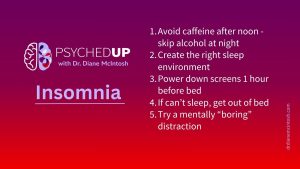

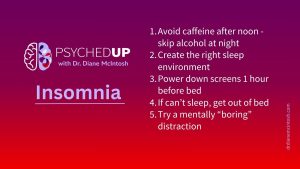

Struggling With Sleep? Here Are My Top Five Tips for Better Rest

I want to share my top five “sleep hygiene” habits that can support healthier sleep. They won’t solve chronic insomnia on their own, but they are essential ingredients for better rest.

When Nadia’s Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) became almost paralyzing, the mother of two realized she needed help.

Flooded with horrifying scenarios of what might happen to her children – all irrational events that were very unlikely to ever occur – her daily life was filled with what should have been ordinary activities, like taking her kids to the park, that had become so terrifying and overwhelming, she couldn’t face them. And she’d had to live with these symptoms since she was 10 years old.

“It was debilitating,” she recalls, adding she would visualize car accidents, trips to the hospital, the death of her children. She would also relentlessly check and recheck things, like whether the door was locked, the seatbelt was secure or the stove was turned off.

Nadia’s job as a healthcare worker was also suffering. She worried constantly about making a mistake that might harm a patient—second-guessing her decisions about the most routine issues, over and over, when she returned home after work.

“I couldn’t relate to other people and other people couldn’t relate to me. I felt really isolated and alone,” Nadia says. “I didn’t know what was wrong with me,” she recalls.

OCD, which affects 3% of the population, is a mental illness characterized by unwanted thoughts and fears. Obsessions are intrusive thoughts, images or impulses that are unwanted and provoke distress. Most people experiencing compulsions try to suppress or neutralize them by performing repetitive, purposeless behaviours or mental acts, called compulsions. And unfortunately, without treatment, obsessions and compulsions associated with living with obsessive compulsive disorder are impossible to stop. These symptoms can hold people captive in their homes, unable to perform daily tasks, form healthy relationships or even hold down jobs.

A common obsession theme is the fear of contamination or infection. The corresponding compulsion may be to wash their hands, sometimes hundreds, even thousands, of times a day. Creating and following strict rules around order, checking, counting or repeating numbers, phrases or thoughts are also common compulsions, which might not seem connected in any way to a specific obsession. Obsessions are commonly focused on taboo subjects, such as sexuality or religion. At its core, obsessions are most commonly associated with harm- not a wish or desire to harm anyone, but a thought that you could, or a fear that harm will come to you or someone you love.

“OCD is one of the most challenging disorders I treat,” says Dr. Diane McIntosh, psychiatrist, founder and CEO of RAPIDS Health.

With OCD, “The thoughts are always inappropriate and unwanted — I call them ‘sticky thoughts,’” says Dr. McIntosh.

“Fear of causing irreparable harm is very common in OCD, thinking about things such as provoking an accident or having repeated intrusive thoughts that you might cause a wildfire that could destroy your town,” she says.

“A loving new mother with OCD might have an obsessive thought that she could put her baby in the microwave, but it’s the last thing on earth she’d want to do or ever act on. Of course, the thought is terrifying and isolating. She doesn’t understand why she’d even think of such a thing. And who is she going to tell? She would fear her baby would be taken away.”she says.

Like most mental illnesses, people with OCD usually have insight – they realize their obsessions are irrational, says Dr. McIntosh. At the same time, they are powerless to stop them, even though the thoughts are negative and cause anxiety and distress.

“You’re living two different lives, because there’s your life that you present to the world, where you hope that no one notices that you’re having all these weird thoughts,” says Nadia. “And then there’s your inner life, where things are just awful and chaotic and sad and frustrating.”

Diagnosing OCD is not easy, because patients are often afraid to share their symptoms. “I’ve spent a year with a patient before I’ve even recognized that they have OCD,” says Dr. Randy Mackoff, a Vancouver-based clinical psychologist.

“A real challenge when diagnosing OCD is that patients rarely share every symptom,” says McIntosh, “because obsessive thoughts can be deeply embarrassing, even horrifying, preventing many people with OCD from disclosing them.

Arriving at a diagnosis of OCD comes down to building a safe therapeutic relationship and using specialized questionnaires, says Dr. McIntosh. “There are no useful blood tests or brain scans, so we use clinical scales that have been studied in large populations, so we do know they’re highly likely to pick up the diagnosis of OCD and to quantify its severity,” she says.

Some questionnaires are self-administered, while others are conducted by a healthcare provider.

The sooner OCD is diagnosed, the sooner the journey to recovery can begin. “It’s really important for people with OCD to know that the sooner they get treated, the less intense it’s going to be, and the easier it will be for them to get better,” says Nadia.

As with all mental illnesses, “the earlier that you can intervene, the less likely it is that you’ll need a more complicated intervention,” says Dr. McIntosh.

Drs. Mackoff and McIntosh agree that treatment for OCD includes medication, such as antidepressants and antipsychotics, as well as talk therapy, especially cognitive behavioral therapy. “From a psychologist perspective, it’s not about eradicating all the symptoms — it’s so they don’t interfere in the really important areas of functioning in someone’s life,” Mackoff says.

Other techniques include developing self-soothing skills, learning to effectively deal with distress and learning emotional regulation. Treatment is determined by, “the difficulties that the person is experiencing, as a result of their obsessions and their ritualistic behaviors,” says Dr. Mackoff, who adds that he commonly employs visualization and helps his patients to slowly be exposed to fear-inducing situations in their real environment. Ultimately, he says, “we examine what’s working and what’s not working,” so the treatment is tailored to each individual’s unique needs.

A specific kind of cognitive behavioural therapy that has been very effective for OCD is called exposure and response prevention (ERP), says Dr. McIntosh. One example of ERP is repeatedly exposing a patient to thoughts or situations that elicit compulsions.

“I think of an ERP therapist as being like a highly skilled electrician – they work with you to replace the bad neuroplasticity – the faulty wiring that leads to and reinforces compulsive behaviors – with new wiring that sets their patients free of those compulsions,” she says.

In the case of compulsive checking, a patient’s brain might be wired to check the stove. Every time they do, the strength of the wiring is reinforced. Through ERP, when the patient is repeatedly exposed to the stove but doesn’t check to see if it’s on, the wiring becomes less strong and the drive to check eventually diminishes.

Re-training the brain isn’t easy. “It’s hard work,” says Dr. McIntosh. Involving supporters in her patient’s care is critically important, she adds, including a family member or close friend, at her patient’s discretion, to help support their recovery. “Just to have another person hearing this story can be really, really helpful,” she says, because it’s a challenging path to recovery, so we need all hands on deck!

Nadia struggled through her 20s until she met her current psychiatrist and was prescribed medication – some of which worked, while others did not. She also underwent CBT. “Once I figured out all the things that were wrong and was able to treat them appropriately and things got a lot better,” she says.

“After I got on the right medication and I was getting the right help, I was able to form a meaningful relationship, get married, have kids — all the things I never thought I would be able to do in my life,” she says.

“If you have OCD symptoms, try to get help right away.”

Listen to This is OCD episode of the PSYCHEDUP podcast.

This blog post is part of a series looking at the state of our mental healthcare system and ways we can create sustainable change to improve quality and outcomes for anyone impacted by mental illness.

I want to share my top five “sleep hygiene” habits that can support healthier sleep. They won’t solve chronic insomnia on their own, but they are essential ingredients for better rest.

There’s something about flipping the page on the calendar from December to January. For many of us, the beginning of a new year represents a clean slate. So, if you find yourself in the mood to take that time to pause and reflect after the holidays, here are a few tips on making smart New Year’s resolutions.

The holidays can be stressful. Here are a few thoughts on how to make the most of what can be a most wonderful time of the year.

Please provide your contact information in the form below. It helps if you provide enough detail in your message so we can help. We look forward to hearing from you!

Thank you for your message. We will respond to your email promptly.